Chapter 2: How are VC funds organised?

Listen to the audio version here:

In our previous blog post, we covered where startups can find money, and we shared that venture capital funds (VC) make up the majority (74%) of venture capital investments in Europe. Here, we explain how they are structured, to help you fundraise smartly.

VC fund structure

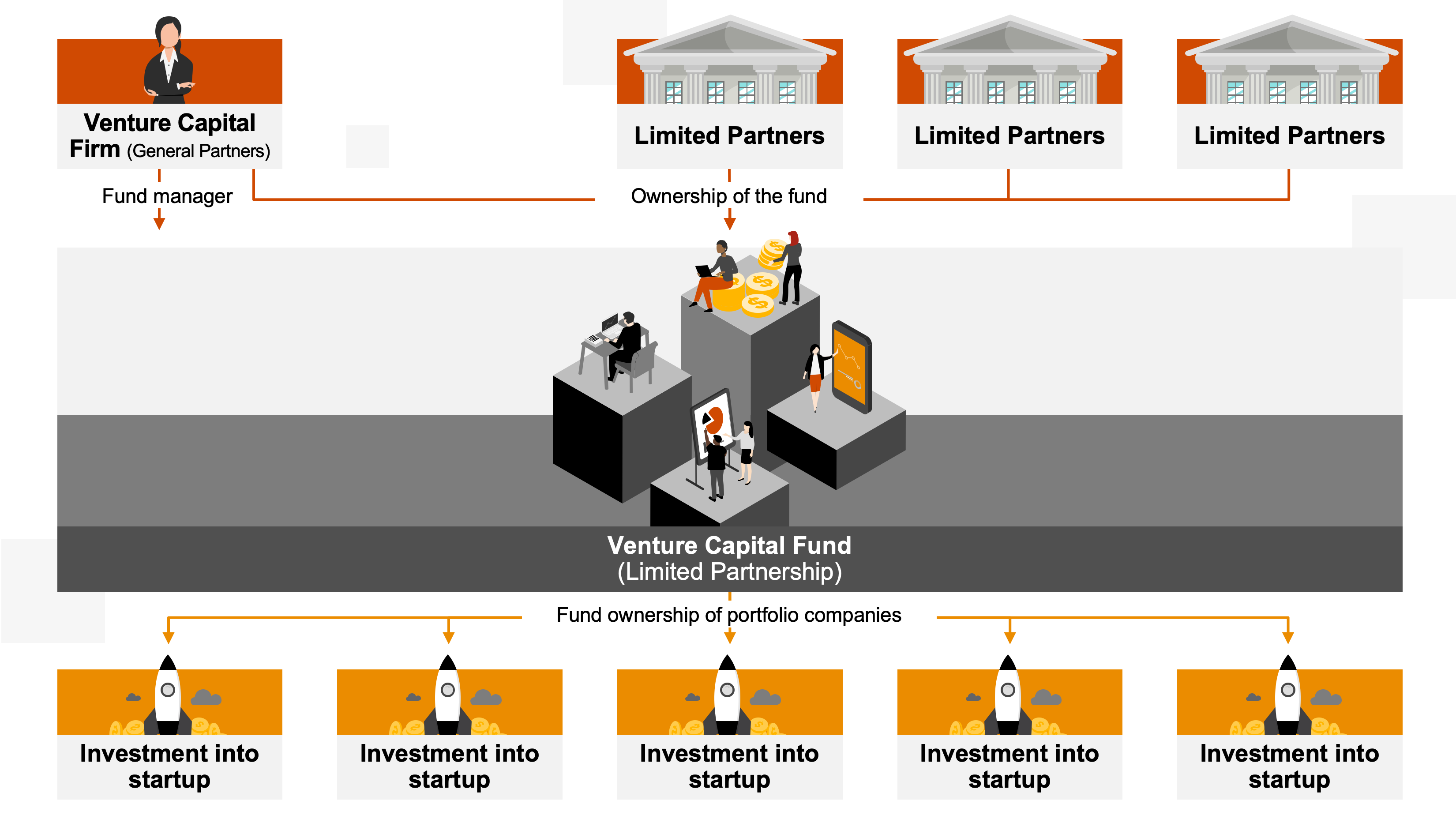

Generally, VC funds involve three main stakeholders: limited partners (LPs), general partners (GPs) and portfolio companies (Figure 1). Limited partners invest in VC funds and are usually not involved in the fund’s daily management and operations. Limited partners could be pension and insurance funds, wealthy individuals and family offices, corporates, banks, governments, etc. General partners, on the other hand, are in charge of the daily operations of the fund, including sourcing deals, investing, hiring, monitoring, portfolio management and other day-to-day administrative activities. They are often supported by a team that may include investment managers, associates, startup scouts, etc.

Just like entrepreneurs, GPs have to go through a fundraising process to raise capital from LPs for their fund. Once capital has been raised, GPs are guided by an investment mandate that details the scope and objectives of the fund. This investment mandate can include geography, the type of companies or industry, as well as the size of each investment.

Figure 1: The VC fund structure

Open-end vs closed-end funds: VC funds can be structured as either open-end funds or closed-end funds. These fund structures have some similarities, but they also have differences that affect your startup. We explain the key differences of each structure in Table 1.

Table 1: Difference between open-end and closed-end funds

Definition |

Closed-end funds |

Open-end funds |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Lifecycle of fund |

Length of time in which the fund exists. |

The fund has a fixed term and typically lasts 10–15 years. |

There is no fixed term: can last for as long as required. |

Fundraising period |

The period where GPs raise capital from LPs for the fund. |

Typically a fixed fundraising period, usually 12–18 months. |

Can continually raise capital throughout the life of the fund. |

Investment period |

The period where raised capital is invested in startups. |

There is a fixed period when investments are expected to be made. This is typically the first 4–6 years of the lifecycle of the fund. |

There is no fixed investment period and investments can be made at any time during the lifecycle of the fund. |

Harvest period |

The period where there is an expected return on investments. |

There is a fixed harvest period, usually starting between the 5th and 6th year of the fund. Funds are expected to start having some exits (i.e. acquisitions, IPOs, etc.). Proceeds are expected to be received and distributed to LPs before the end of the fund lifecycle. |

There is no fixed harvest period and returns and proceeds can be distributed to LPs at any time. Proceeds are not always determined by exits. |

Performance fees |

Fees charged based on the return on investment. |

Performance fees are often represented as ‘carried interests’ which are paid to GPs when returns have been realised through an exit (e.g. IPO, M&A, etc.). |

Performance fees are based on increases on the net asset value (NAV) of the fund. |

Management fees |

Fees essentially used for the day-to-day operations of the fund. They can be deployed to hire additional staff, and cover marketing and other operational expenses. |

GPs typically receive management fees based on capital commitments during the investment period and invested capital after the investment period. |

GPs charge management fees based on either net asset value (NAV) of the fund or invested capital. |

Although each fund structure has its benefits, startups usually choose a VC fund based on preference, needs, connection to the VC, growth stage, etc. A key benefit of open-end funds is that they have a long-term investment horizon and can therefore partner with startups for as long as necessary. Closed-end funds, on the other hand, have a shorter term investment horizon, which sometimes leads to increased pressure to pursue an exit sooner. However, we see this exit pressure being mitigated lately by roll-over funds. Roll-over funds enable VC funds to have a longer and flexible lifecycle, by having a non-fixed fundraising period.

PwC Pro Tip

- VCs have an often strict investment mandate, so do your homework before reaching out to a VC. If your company does not fit the mandate, you’re probably wasting both your own and their time. .

- The decision makers at the fund are the general partners. It’s always helpful to build a good relationship with these individuals alongside other junior contacts in the fund.

- It's important to know the structure of your target fund and its lifecycle as this can help you determine if there is available capital for your startup.

- When searching for the VC fund that’s right for you, it’s worthwhile to evaluate each fund holistically (i.e. looking beyond the fund structure alone and considering other added value services).

How VCs evaluate investment opportunities

As highlighted earlier, GPs invest on behalf of LPs via the VC fund, so its their responsibility to minimise risks associated with investing in high growth companies. GPs minimise this risk by evaluating some key company characteristics, outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Key characteristics that VCs evaluate to minimise investment risk

| Characteristics | Description |

|---|---|

Team |

Must have a diverse and complementary team with subject-matter expertise in the industry of operation. |

Product |

Must have a product or solution that solves a real problem. |

Market size |

The market must be large enough to support the startup’s growth and expansion. |

Traction |

Must have some evidence that the product is needed by its target customers. |

Value proposition |

The product must be unique, and can be differentiated from the competition. |

Defensibility |

There should be some way of maintaining the startup’s competitive advantage. |

Business model |

The company should have a clear way of generating revenues and profit. |

Looking at returns, VC funds have a high probability of experiencing significant losses within their portfolio. Therefore, they put a lot of effort into finding and investing in startups that can generate enough money to return the capital raised from LPs plus profit. Although VC funds’ expected return varies across industries, geographies, risk profiles, etc., they usually aspire to a gross internal rate of return of around 30% (Source: Investopedia).

In the next blog post we’ll look at the fundraising process.

For more information on how PwC can support you in your fundraising, and how we support startups and scaleups, visit our website.

Download the full PwC's fundraising whitepepaper here

Where can Startups find money?

The fundraising process

Overview